Hi everybody!

This post is unlike any that have appeared on this blog, and it's likely to ruffle some feathers...but if one assumes good will, and goes into it with an open mind, one may find it quite thought-provoking.

I think that parts of her treatment are a little heavy-handed and overly broad; but overall, I think she make some well-reasoned points - including something that bugged me as a child..."Why must the Indians be the bad guys?"

Regardless of how you feel about her analysis, it is very thought provoking, and any information on the great man - Louis Marx - is always appreciated.

This is a very long excerpt from a 2010 University of Michigan Doctoral Dissertation, by doctoral candidate Sarah Gould Zenaida entitled:

---

Toys Make the Nation: A History of Ethnic Toys in North America.

Louis Marx and Company, often referred to as Marx Toys, was by far the twentieth century’s most prolific manufacturer of Western playsets. Marx introduced its first western playset, the Fort Apache Stockade, in 1951, and by the time the company closed in 1978, it had produced “over 250 standard variations of Marx Western playsets,” including many television and movie tie-in sets.71 The Western playsets nearly always included figures representative of “good guys” and “bad guys.” Typically this broke down into cowboys and Indians, though occasionally the bad guys were white outlaws or, in the case of Alamo themed playsets, Mexican soldiers. The Western playsets were not

205

the first time Marx confronted ideas about ethnic and racial Others in their toys, in fact one of the first two toys Marx manufactured was the Alabama Coon Jigger, a mechanical tin toy featuring a dancing African American minstrel.72 Louis Marx, the co-founder (with his brother David), president, and face of Marx toys did not invent the Alabama Coon Jigger. In 1921, he purchased the die for the toy from his former employer Ferdinand Strauss.73 The Ferdinand Strauss Corporation, the first American company to mass produce pressed tin mechanical toys,74 along with German exporter Lehmann, made Alabama Coon Jigger toys throughout the first twenty years of the twentieth century. However, these Alabama Coon Jiggers were merely variations of the dancing minstrel toy, which have existed since at least the 1880s when Ives produced a version made of wood and cloth. That Marx started his own toy company with an Alabama Coon Jigger toy is telling of the centrality and appeal of ethnic and racial imagery in American toys, as well as Marx’s openness to such imagery in his toys.

Though Louis Marx would come to be known as the “Toy King,” and “the Henry Ford of the toy world” due to the success of his cheap, mass produced toys, he came from humble beginnings.75 Marx was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1896 to Jacob and Clara Lou Marx, immigrants from Germany.76 His father was a tailor and his parents also tried their hands at running a dry goods store, but they were unable to keep their businesses afloat.77 Louis grew up so poor that, “his parents could not afford to buy a single toy for their son.”78 At sixteen years old, Louis got a job with Ferdinand Strauss, and proved to be a natural for the toy business, quickly working his way up to factory manager by the time he was twenty.79 The Marx brothers set their sights on bigger things and established their own toy company in 1919. They started out as “middlemen,” connecting

206

manufacturers to retailers, and grew to become “the world’s largest manufacturer” of toys by 1950.80 When the Toy Industry Association, Inc. (the American toy trade association formerly known as the Toy Industry of America) established a Toy Industry Hall of Fame in 1985, Louis Marx was the first inductee.81

In terms of a rags-to-riches story, there are many parallels between Louis Marx and Beatrice Alexander, however, they had a very different engagement with politics and the social meaning of their products. Though the Marxes were apparently Jewish,82 Louis was neither a practicing Jew – he declared himself agnostic in an interview with Time Magazine - nor active in the Jewish charities supported by other members of the toy industry.83 The American toy industry had a strong Jewish presence in the first half of the twentieth century, with Jewish Americans leading several of the nation’s top toy companies, including the Ideal Novelty and Toy Company, The Lionel Corporation, American Character Doll Company, and the Alexander Doll Company. The United Jewish Appeal of Greater New York even had a Toy and Doll Division whose annual banquets were regularly reported on by the toy industry journals Playthings and Toys and Novelties in articles that read like a who’s who of the toy industry. These events appear to have been golden opportunities for networking and business deals. In addition to representatives from major toy companies, representatives from department stores such as Gimbel Brothers, Hecht Brothers, R. H. Macy & Company, and Bloomingdale Brothers participated on a buyers’ committee. Even as a non-practicing Jew, these events and the causes they supported – primarily promoting positive relationships between Christians and Jews and raising money for Israel – would have been good for business, but it seems that Marx had little interest in them. Louis Marx was known to wine and

207

dine buyers, but he apparently preferred the 21 Club to public banquets. Marx was also charitable, regularly donating Christmas toys to poor and orphaned children.84 But while Alexander wanted her high-end dolls to expand a child’s world, foster an appreciation of literature, and serve as a child’s friend, Marx emphasized inexpensive sturdy toys with a familiar, easy to follow play script that could entertain a child for hours.85 Both Alexander and Marx were concerned with profitability, but Alexander might be understood as having more socially conscious expectations for her dolls, while Marx simply wanted his toys to appeal to the masses.

Marx’s early toys were tin mechanical toys in the style of earlier Ferdinand Strauss toys. These toys were whimsical and inexpensive, and they were often recycled with minor cosmetic changes made every few years to maintain their novelty appeal. Marx toys were primarily sold through national chain stores and mail order companies such as Woolworth’s, Walgreen’s, Sears, J.C. Penney, and Montgomery Ward.86 Because most of Marx’s orders were placed by these high volume chain stores (ninety percent in 1955), the company had few overhead costs related to recruiting retail buyers, which helped keep toy prices low.87 In 1946, seventy-five percent of Marx’s sales consisted of toys ranging in price from ten-cents to one dollar.88 By the 1950s Marx toys were slightly more expensive, but most fell within the range of slightly less than one dollar to about six dollars for a deluxe playset. The most expensive Marx toys rarely surpassed the ten-dollar mark.89

The 1950s were the Golden Age of Louis Marx and Company, aided by the popularity of playsets. Improvements in plastic composition and molding technology, the Western craze, and the growing number of children after World War II all contributed to

208

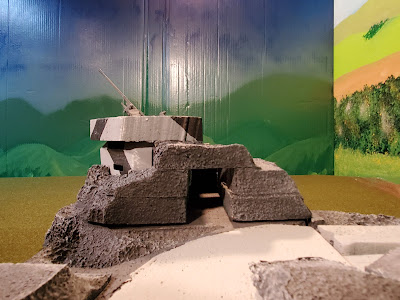

Marx’s success in selling inexpensive plastic playsets designed to primarily appeal to boys. Marx’s Western playsets emphasized play scenarios in which white cowboys, soldiers, or frontiersmen defended themselves against attacking Indians. The Fort Apache Stockade, the original Marx Western playset and model for future Western playsets, consisted of a log cabin made of lithographed tin, panels of log fencing to be erected around the cabin, two block houses to fit onto ninety-degree angles in the fencing, two tepees, thirty Frontiersmen, thirty Cavalry soldiers, thirty Indians, four horses, plus accessories such as ladders, trees, wagon wheels, a water well, axe and chopping block, butter churn, powder kegs, two totem poles, and a flag post with a US flag. Everything except the cabin was made of injection molded plastic, so that a 100-piece playset retailed for less than six dollars in 1957.90 In addition to being quite affordable, Louis Marx’s nephew Charles Marx has speculated that parents liked Western playsets for their educational value, and claims that, “children could not help but learn about history through their exposure to the classic themes used in [them].”91 However, the version of history they might have learned was likely fairly inaccurate.

Fort Apache is a real place. It was a late nineteenth century US Army Cavalry post located within a still active Indian reservation of the same name in eastern Arizona.92 It was also the site of a battle between the Cavalry and White Mountain Apaches in 1881. In 1948, film star John Wayne starred in a movie titled Fort Apache about tensions at a US Cavalry post. Despite its name, the film was not about the 1881 battle at Fort Apache, but rather a “last stand” battle between the Cavalry and the local Indian population that was loosely based on the Battle of Little Big Horn.93 Historical inaccuracies aside, the idea of a “last stand,” an epic battle between two conflicting sides that can be reenacted

209

over and over again with tiny figures with tiny weapons is one that has immense play value. As Charles Marx has also noted, despite whatever parents hoped children might learn from these playsets, children ultimately had their own reasons for playing with them. A close look at the details of Marx’s Western playsets reveals part of their appeal.

A fully erected Fort Apache playset would have taken up a good amount of floor or table space. In addition to the fort surrounded by a long log fence, the set came with an “Indian camp” consisting of tepees, a camp fire, and strangely enough, totem poles. Though the Indians in Western themed toys invariably wore clothing associated with the western plains, totem poles, tall carved sculptures made from trees, are most associated with the Pacific Northwest. This confusion of cultural practices is not surprising given that the designers of such toys did not seek authenticity; rather they sought familiarity. Children of the 1950s had likely seen totem poles in photographs, magazines, or comic strips. While children may not have known their exact origins, it is likely that children would have at least known totem poles were Indian related. So though totem poles really had no place in a Western Indian Camp, in these playsets they added to a fantasy understanding of Indian life. The Indian camp also served as a visual contrast to the fort. The fort’s inhabitants had a large log cabin, while the Indians had small tepees. The fort had a large fence around it, while the tepees had no fortification. The fort was equipped with domestic items like a water well and butter churn (because even in the Wild West men need butter), and the Indians had a campfire with a kettle. Both parties had a least one woman in their ranks. A woman reloading a rifle accompanied the Cavalry, and a woman kneeling on the ground and another standing with a large bowl accompanied the Indians. Though these playsets were marketed for boys’ play, their designers included

210

small aspects of domestic life in Fort Apache. However, they also included a great deal of gruesome detail.

Nearly all of the playset’s toy figures carried weapons and were posed as though engaged in battle. The frontiersmen and Cavalry soldiers usually bore rifles or pistols, though occasionally Cavalry soldiers wielded swords. One Marx Indian held a tomahawk in his right hand and a scalp in his left. A mold for casting the toy figures might have anywhere from one to over one hundred cavities – slots into which the plastic was injected. Molds were typically designed to match up with a particular set or related sets. For example, a mold with eighteen cavities for various Cavalry soldiers was used for the Fort Apache Stockade (1955-1977), the Custer’s Last Stand playset (1955-1972), a Rin- Tin-Tin Cavalry set (1956), an Indian and Cavalry set (1969), and several stand alone Cavalry sets (1956-1968).94 It was incredibly costly to develop a new mold, and the thematic similarity of so many of Marx’s playsets made new molds for every Western playset unnecessary.95 Thus, the Indian with the scalp was likely included in numerous playsets, along with Indians with knives, Indians with rifles, Indians with bows and arrows, and Indians with clubs. One shared characteristic of nearly all the Indians was their relative lack of clothing compared to the Cavalry soldiers and frontiersmen.

Though a play script of Cavalry soldiers and frontiersmen defending the fort against invading Indians was encouraged by the Fort Apache playset’s box illustrations which showed angry Indians trying to scale the walls of the stockade, and catalogs like the Sears Christmas Wishbook which suggested, “He can help the 30 heroic Frontiersmen in their desperate fight to hold the fort against 30 attacking Indians,” children would have ultimately followed whatever play scenario suited them. However, certain ideas about

211

Indians, frontiersmen, and Cavalry soldiers were designed into the figures themselves. The Indians occasionally held rifles, but mostly used more “primitive” weapons. Nearly all of the Indians are shown shirtless, with either a loincloth or buckskin pants. Some have hair braids and others Mohawk style haircuts. Most have one to three feathers on their heads. In contrast, the Cavalry soldiers wear uniforms with belts and buttoned shirts. They have “modern” weapons. Most wear a hat. The frontiersmen bear similarities to both the Indians and the Cavalry soldiers. They wear buckskin pants like some of the Indians, but also buckskin shirts to provide full chest coverage. They also wear fur “coonskin” hats and they carry rifles. Markers of modernity are much stronger with the Cavalry soldiers and frontiersmen, even though the frontiersmen have adopted some wilderness elements to their attire.

Frontiersman Davy Crockett and his coonskin hat were catapulted to icon status by a series of live action television specials by the Walt Disney Company beginning in late 1954. By the following spring, stores had sold over one hundred million dollars of Davy Crockett merchandise, some of which was earned by Marx.96 Taking advantage of the Crockett craze, in 1955 Marx released a Fort Apache Stockade with “Famous Americans” added to the figures. Kit Carson, Buffalo Bill, General George Custer, Sitting Bull, Daniel Boone, and of course Davy Crockett were miniaturized and thrown into the Fort Apache set with no explanation as to why they might be there. Marx also made a Davy Crockett Frontier playset and a licensed Walt Disney Davy Crockett at the Alamo playset that same year. The former included a plastic ranch house with a white fence a Davy Crockett figure wearing buckskin and a coonskin hat, ten cavalry soldiers, and twelve Indians.97 The latter included a lithographed tin Alamo and lithographed tin wall

212

sections designed to look like adobe. In keeping with the story of the Alamo, the toy figures consisted of one Davy Crockett figure, thirty “attacking” Mexican soldiers dressed in army uniforms with distinctive round infantry hats, and thirty “stalwart” frontiersmen.98 The set also included five cannons, eight horse, trees, ladders, and a tiny replica of the flag that was flown at the Battle of the Alamo.

In this playset, as dictated by Disney’s “Davy Crockett at the Alamo” television special, the Mexican soldiers replaced Indians as the bad guys, with the frontiersmen still in the role of good guys. Historians Randy Roberts and James S. Olson have described Disney’s representation of the Mexican Army as that of a “horde;” the Mexicans were “nameless and faceless, indistinguishable from another.”99 This is true of many bad guys and apparently caused some confusion at Marx, as some Davy Crockett sets inexplicably replaced the Mexican soldiers with Indians. But the confusion did not stop with the bad guys; good guys were interchangeable too. The specification sheet for a Davy Crockett Alamo set in 1956, listed one set of “PL-443 Indians (12-pieces)” along with one set of “PL-442 Cavalry Figures (10-pieces).”100 One outcome of this interchangeability of the different groups of good guys and different groups of bad guys is that a racial division becomes apparent. The good guys are white and the bad guys are not. This is a pattern that existed in Marx’s basic cowboy and Indian sets from at least 1956 - those sold with a small cabin in place of a stockade, tepees, covered wagons, canoes, horses, cowboys with cowboy hats, lassoes, and pistols, and Indians with tomahawks and bows – until 1975 when a black Cavalry scout named Jed Gibson was added to Marx’s Johnny West Adventure action figure series.101 Jed was only available for one year. By the following

213

year the Western craze was over, and the Johnny West series rode off into the sunset barely acknowledging the near blanket whiteness of toy Western heroes.

Conclusion

Toy makers have used outsider groups as targets of aggression in toys since the late nineteenth century,

---

Whew! I gotta go lie down.

My toy soldier activities remain dormant until May - when the current semester ends. I hope to turn my attention to finishing the background painting for the Navarone scenario, which I'd really like to do multiple posts on this summer.

Until then,

Enjoy the weather and...

Soldier on!

Mannie

very near the beginning of American manufactured toys. These toys have been most often marketed as boys’ toys, and thereby have participated in the construction of an ideal masculinity for boys that is supported by the oppression of racial Others. By promoting play in which outsider group members are appropriate targets of masculine aggression the toys may have desensitized children to violence and dehumanized people of color in white children’s eyes, turning them into make-believe characters rather than real people.

Mannie -

ReplyDeleteThat was a most interesting read. From my own experience with boys' play that in boys' play 'cops and robbers', 'cowboys and indians', goodies and baddies' one started out wanting to be the 'good guy', but after a while chose to be 'the other'. That was probably a good thing. A non-Kiwi might have supposed there would have been 'Settlers vs Maori' games, but not only did that never happen, so far as I know, no one ever thought of it. Maybe it was because we were so used to living among each other.

A few years ago, I acquired a pack of Army Men labelled 'Good Ol' USA vs Red COMMIES'. The company was based in Seattle; the figures made in China. The final irony? I painted them up exactly the same to form an infantry 'company' in the service of the fictional Ra'esharn Empire.

Cheers,

Ion

A very interesting read Mannie, nothing too surprising, but nice to see it get an academic treatment - the Totem pole 'thing' is far from exclusive to Marx though, name a British, German, French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, or US maker who got it right!!

ReplyDeleteYou know a bit of text as gone awry at the bottom of the post?

H

The Westerns through that time were actually mixed in sympathy for the Indians and a common theme was that bad individuals on both sides caused hostilities.

ReplyDeleteThe method of native warfare and culture included torture and mutilation of captives which had a lasting influence on settlers perception of the Native Americans. Of course, the reciprocation of scalp taking and atrocities against the natives such as Sand Creek gained less publicity but they are still touched on in Westerns, so in theory, children could perceive the Indians as good guys heroically resisting invading whites. John Wayne's 'The Searchers' summed up the horror of being captured by the 'Hostiles' although the horror was much worse than depicted with daily rape, beatings and torture of females captured.

The reality is that humans are 'tribal' even when civilized, and so tend to identify with their own race or culture. I can't remember ever wanting to be the Indians in my childhood games. Then again the soldiers and cowboys had the advantage of a wooden fort and a cannon which it made it harder for toy Red Indians to win..